Too Much Horror Business

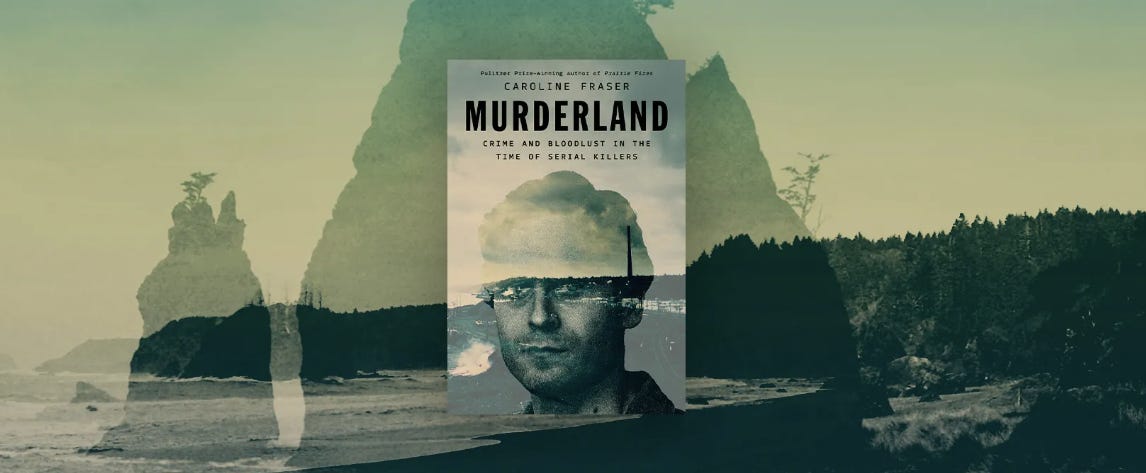

A Review of Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers by Caroline Fraser

“They and the books called scholarly are taken as signs of a knowledge explosion. It is only a knowledge inflation. The knowledge which should go into a footnote of six lines is made into an article of twelve pages, and that which should go into an article of twelve pages goes into a book of three hundred.” - Jacques Barzun

Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers by Caroline Fraser is a deeply frustrating book. It has three parts. One third of the book is a more or less chronological history of various serial killers who were active from the 1960s up to the early 2000s. Another third of the book is a history of industrial pollution in America and especially in the Pacific Northwest, where a disproportionate number of these serial killers have been from. And the final third is the author’s personal reminiscences of growing up in that area during the 70s and 80s. Each section on its own is more or less ok—it’s the effort to connect them that is problematic.

My first impression was that the personal storyline was wholly unnecessary and a classic example of female solipsism and narcissism on display—ironic for a book focused on the extremes of male narcissism in violent psychopaths. By the end I changed my mind somewhat, because I also grew up in this era and I remember very well how serial killers were just a normal part of the nightly news. I had no idea that they were not always so prevalent. I remember, when the Night Stalker was active, asking my parents if he would come and get us. No, they explained—he’s in California, and we live in the Midwest. Oh. But later, some other guy was breaking into the homes of elderly people in my home city and killing them for no apparent reason. My father gave my grandfather a shotgun, which he kept in the bedroom closet for a year.

Growing up like this, during what more than one writer has called “the golden age of serial killers,” affects you, and I understand wanting to write about it. When I eventually found out that there were not always this many psychos prowling around, and that there doesn’t seem to be as many now as there were fifty years ago, I wondered why. What caused the number of serial killers to rise so dramatically in the 60s, 70s and 80s? And what caused the number to decline after that?

Penguin Books is advertising Murderland as though Caroline Fraser has an answer to these questions, but she doesn’t. What she does have is an intriguing idea that she unfortunately does not bother to form into a real hypothesis, much less try to prove. Her theory is never explicitly stated in the book, although it’s insinuated time and again. It is more or less given by the publisher on the book’s webpage: “At ground zero in Ted Bundy’s Tacoma stood one of the most poisonous lead, copper, and arsenic smelters in the world, but it was hardly unique in the West. As Fraser’s investigation inexorably proceeds, evidence mounts that the plumes of these smelters not only sickened and blighted millions of lives but also warped young minds, including some who grew up to become serial killers.”

Elevated blood levels of lead and other toxic metals as a cause or contributing factor of psychopathy. As someone who studies the work of Ray Peat and others on how hormones, nutrients and toxic substances (including pharmaceuticals) can affect the mind for better or worse, my interest was immediately piqued. I am also familiar with the work of Dr. Carl Pfeiffer, author of Nutrition and Mental Illness, who studied the effects of heavy metal toxicity and mineral imbalances on criminal behavior, and whose ideas have led to novel treatments for autism. I thought surely Dr. Pfeiffer’s work would be mentioned in Murderland, but it’s not. Fraser mentions numerous studies showing that exposure to lead can cause a litany of health problems, including violent behavior, and how the CDC has been steadily revising down their “safe limits” of lead in the blood—there is no safe limit, any amount is harmful—but she doesn’t go into any specific theories of how lead or other toxic metals or chemicals might form part of the larger causal matrix that creates serial killers.

It should be obvious to anyone that if lead exposure was all it took to create a psycho killer, we would have a lot of more of them than we do. In the sections of the book which deal with the history of industrial pollution, Fraser shows how large sections of the country—millions of people—have been contaminated and poisoned with these substances. This raises the question: why do only a small number of these millions become psychotic killers?

In the 1980s, the religious right put forward the idea that pornography caused serial killers. Just before he died, Ted Bundy gave an interview to James Dobson in which he claimed that violent porn is what led him to become the monster he became. The Christian Coalition and like-minded groups seized on this and still show this interview as proof of their claims (you can find it on YouTube), while defenders of porn like Al Goldstein, as well as those who are just skeptical of anything and everything Bundy says, dismiss it as Bundy rationalizing and displacing responsibility for his crimes, as he always has in one way or another.

In my opinion, both are partly right. Bundy was unquestionably a narcissist and a liar who shifted blame away from himself. But he was also known to have been an avid reader of True Detective magazine and probably others like it, which regularly featured explicit, violent sexual content in story form in the days before the internet made such things available right in everyone’s homes. Nowadays many people are not aware of just how much material was produced which described or depicted, in lurid detail, violence against women, including extremes of torture and murder. To give just one example, you can look up the story behind Nights of Horror magazine, which was produced in the 1950s and sold in smut shops in Times Square and elsewhere.

It’s somewhat famous, or infamous, for two reasons: firstly because it was illustrated by Joe Shuster, co-creator of Superman, who apparently needed some cash and so did the job anonymously, and secondly because it was banned after it was believed to have inspired a real life killing spree by a group of teenage boys who became known as the Brooklyn Thrill Killers.

Now to claim, as some religious conservatives still do, that “pornography creates serial killers” is simplistically stupid and a shortcut to thinking, which we know because millions and now probably billions around the world consume pornography and don’t become serial killers or anything like it. This isn’t to say that porn is harmless, but it’s not mass producing Ted Bundys. However, if we want to look at the issue seriously, that kind of blanket dismissal won’t do. We have to distinguish between violent and non-violent pornography, just for starters. When we look at the consumers of violent porn, we still don’t have anything like a direct cause and effect relationship—most consumers of it will not act out violence in real life. But we also cannot ignore cases like the Brooklyn Thrill Killers, or Richard Cottingham (the “Times Square Torso Killer”) or Ted Bundy or Richard Ramirez, who did consume this material and who did act out similar scenarios in real life. It seems a reasonable hypothesis that violent pornography can and sometimes does act as a trigger for men who also have other risk factors for engaging in violent sexual behavior. Some of those other risk factors are: broken families, suffering abuse and/or neglect in their childhood, suffering head injuries that may have caused brain damage. With all of these risk factors, there is nowhere near a 1:1 cause and effect relationship that guarantees becoming a serial killer. But it seems reasonable to posit that the more of them a man has in his background, the more likely he is to be prone to violent behavior.

None of this nuance is present in Murderland. What Fraser does instead is paint a portrait of a country poisoned by industrial pollution and also haunted by crazed serial killers, then leap immediately to “America is haunted by serial killers because it was poisoned by industrial pollution.” She seems to be more interested in drawing a moral equivalence between what men like Ted Bundy and Gary Ridgway do and what corporations like ASARCO do than with scientifically establishing the relationship between heavy metal toxicity and psychopathy. “Corporations can be people, and people can be killers, ergo, corporations can be killers,” she writes. Indeed, even the most prolific serial killer cannot compete with the mass poisoning of millions. But her moral equivalence unfortunately doesn’t stop there. She ends the book with what she calls an “incantation”:

I curse you, you corporate scribes and pharisees, you hypocrites, rubbing your hands over whited sepulchres full of dead women’s bones. You think you’re getting away with it. Just you wait.

I rewrite your Bible, restoring the Gospel of Judith, her with a sword.

I declare this: Do not be about your father’s business. Your father’s business is rape and murder.

Be a witch. Be a bitch. Get in the reversible lane and make time run backwards. Loot the Guggenheim: Cover the walls in stove black and ashes.

Hand the engineers their heads; hang them from lampposts on a floating bridge. Smother a foundling after a great war.

The reviews from the publisher’s page—Penguin, as big as it gets—speaks to how utterly fake the world of book reviews and promotions is: “This is about as highbrow as true crime gets,” says the review from Vulture. Highbrow? As in, cultured and erudite? There is nothing highbrow about this book at all. The writing, while decent, is nothing special. There is no stellar research or insight on display other than the main thesis, which could be summed up in an article if not in one sentence. The parts of the book which relate the chronological history of serial killers from the 60s to the 2010s is largely if not entirely a rehashing and assemblage of content from other true crime books. If the author did any original research or interviews, she does not mention it in the main text.

“Fraser has outdone herself, and just about everyone else in the true-crime genre, with Murderland,” says Esquire. Outdone everyone else in the true crime genre? With a book that neither proves its thesis nor contains any original research on the crimes with which it deals? Do words mean anything anymore? Or have they been reduced to a mere monetary value, purchasable by publishers, so that Murderland can be described by the Los Angeles Times as “A superb and disturbing vivisection of our darkest urges,” regardless of the fact that the book is nothing of the sort nor does it claim to be: the author decidedly does not probe deeply into the psychology of any of these men—her thesis that lead poisoning accounts for some or all of their psychopathy negates the need to do so—nor does she claim that they represent “our darkest urges,” sins for which everyone shares a collective guilt, except insofar as she does quite clearly have a feminist bone to pick with men in general, as the somewhat histrionic final passages of the book make clear.

I am not opposed to ranting and raving, nor to first person memoirs. I also don’t fault the author for her anger as a woman over the fact that there are men who have done these horrible things to women. But if an author wishes to have his or her ideas taken seriously, they should be presented seriously, i.e. with detailed supporting evidence, and without emotionalism or irrelevant autobiography. If I were some sort of hack writer for the chemical industry I might try to use the book’s shortcomings to discredit her thesis. But I don’t disagree with her thesis. It’s precisely because I think there is probably something there that I find the book so frustrating in its lack of effort to prove it rather than merely insinuate it.

I wish the author had focused less on the gory details of the murders, less on autobiography, and more on American culture at large and how it was affected by and came to reflect the rise of serial murder. She mentions films like Silence of the Lambs and tv shows like Twin Peaks, but these are the tip of the iceberg, albeit probably the finest examples that you could point to. I had never thought of Twin Peaks, set in the Pacific Northwest, as dealing artistically with the same phenomenon that Fraser deals with journalistically here, but I think she is right about that (to the extent that any David Lynch project can be said to be “about” any one thing only). Silence of the Lambs has a direct connection to Ted Bundy because Buffalo Bill uses some of Bundy’s tactics—pretending to be injured or handicapped—to lure his victims. Fraser incorrectly asserts that Hannibal Lecter was based in part on Bundy. Quite the opposite, Bundy ended up copying Lecter insofar as he worked with Detective Robert Keppel to try to profile the Green River Killer in 1984, three years after Lecter first appeared doing the same with Detective Will Graham in Red Dragon.

What seems very pertinent to a discussion of the serial killer phenomenon is the rise of graphic horror films, which are usually said to begin with 1963’s Blood Feast by Herschell Gordon Lewis. By the 1970s, the “splatter” subgenre was in full swing, packing grindhouse cinemas and reaching a peak in the 1980s, as anyone old enough to remember visiting the Horror section of Blockbuster Video can attest. In other words, the rise and fall of the films mirrors the phenomenon itself. Jeffrey Dahmer was apparently a big fan of The Exorcist 3 and would watch it just before he would “do his thing” with his victims.

Then there is the rise of horror-themed songs in heavy metal and some other genres. The Misfits made a song homage to the aforementioned Blood Feast, and numerous other songs about killing and serial murder, e.g. “Mommy Can I Go Out and Kill Tonight?” Bands like Slayer also sang about such crimes and their perpetrators. Richard Ramirez the Night Stalker was known to be a huge fan of AC/DC’s Highway to Hell album. None of which is to say that these films and albums caused Ramirez or Dahmer or anyone else to kill. But it is a fact that they found a resonance with them, and that deserves to be looked at more closely. At the very least, the author missed a chance to make a joke that it isn’t heavy metal that’s creating serial killers, it’s heavy metals.

The mystery of how and why psychopathic killers are made is older than the history of industrial pollution, and likely will continue even if we can manage to become a non-polluting species. But I think Fraser’s idea of chemical pollution contributing to the rise of serial killers in the 20th century is intriguing and probably at least partly correct, and so I hope more scientific researchers will do some work on it to better understand the connection.