This is the Introduction to the new edition of Vitalism: On The Tracks of Life by Gioacchino Leo Séra, published by Rogue Scholar Press. It was previously published in abridged form at Mans World magazine. It is here reproduced in its entirety including biographical information on the author.

The term “vitalism” has become somewhat confused in recent years.

In biology, vitalism refers to a set of ideas going back millennia which hold that living beings are distinct from non-living inanimate objects because they contain some sort of non-material life energy, to which different cultures and theorists have given different names. The concept to which vitalism is usually opposed is mechanism. The Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913 states that mechanism

seeks to explain all “vital” phenomena as physical and chemical facts; whether or not these facts are in turn reducible to mass and motion becomes a secondary question, although Mechanists are generally inclined to favour such reduction. The theory opposed to this biological mechanism is no longer Dynamism, but Vitalism or Neo-vitalism, which maintains that vital activities cannot be explained, and never will be explained, by the laws which govern lifeless matter.

Since the distinction between the living and the non-living would seem to be self-evident, vitalism was the dominant paradigm in the human sciences, or proto-sciences, for most of their existence, from the ancient Greeks up to the early modern period, though there have always been dissenting voices such as Democritus and Lucretius, who are seen today as forerunners of mechanism. And it is they, and not their vitalist contemporaries, who inspired the scientific thinkers of the Renaissance, who in turn inspired the founders of modern biology and other sciences, such as Descartes, Newton, and later Darwin.

It was against these mechanist thinkers of the early modern period that a new and more nuanced theory of life energy was asserted in the 18th and 19th centuries. The term “vitalism” was coined by Charles-Louis Dumas in 1800 to refer specifically to the doctrines of Paul Joseph Barthez and the Montpellier School of Medicine. Barthez had developed the concept of the “vital principle” in contradistinction to both the physical body and the soul or conscious mind, a third “thing” (though he could never decide if it was material or not) which bears some resemblance to later ideas of the unconscious developed in psychology.

Barthez wrote:

It seems to me that one cannot help but distinguish the Vital Principle of Man from his thinking Soul. This is an essential distinction, whether one imagines that these two principles exist by themselves and are substances, or whether one supposes that they exist as attributes and modifications of one and the same substance... It makes little difference if one calls the Vital Principle Soul, Arché, Nature, etc., but what is absolutely essential is that no connection is ever drawn between the determination of this principle and the affections that derive from the faculties of prudence or any other faculties attributed to the Soul.

These vitalists—or neo-vitalists, since their ideas were hardly the same as the older and quasi-religious ideas of a mystical life force—made some notable objections to the prevailing mechanist views in science. But ultimately, the existence of vital energy could not be proven to the satisfaction of the scientific method, and today vitalism in the sciences is usually dismissed with Julian Huxley’s witty retort that positing a “life energy” no more explains life than positing a “locomotive energy” explains a train.

So what does any of this have to do with philosophy, and more specifically with Nietzsche? Although Nietzsche’s philosophy is grounded in biology, he did not put forth any specific theory of biology and science. His overriding position was extreme skepticism towards everything—i.e., the scientific method—and he was heavily influenced by Lange’s History of Materialism in his early career, as is especially evident in Human, All-Too Human and The Dawn. Thus to the extent that he takes a side in the mechanism versus vitalism debate, he sides with the mechanists and their skepticism (something which is also true, as we will see, of the author of this book Leo Séra).

The convergence of biological vitalism and Nietzsche comes through Schopenhauer. Schopenhauer, the first great influence on the young Nietzsche, was unquestionably a biological vitalist, as shown by the chapters on “Physiology and Pathology” and “Animal Magnetism and Magic” in On the Will in Nature. Although this belief in a life energy as such did not carry over into Nietzsche’s philosophy, doubtless because it smelled of theology and metaphysics, what did carry over was Schopenhauer’s insistence on the unconscious nature of the will:

this will, far from being inseparable from, and even a mere result of, knowledge, differs radically and entirely from, and is quite independent of, knowledge, which is secondary and of later origin; and can consequently subsist and manifest itself without knowledge: a thing which actually takes place throughout the whole of Nature, from the animal kingdom downwards …

[K]nowledge with its substratum, the intellect, is a merely secondary phenomenon, differing completely from the will, only accompanying its higher degrees of objectification and not essential to it …

Thus for Schopenhauer, as for Barthez, neither the conscious volition nor the intellect are the same as the will, or life principle. For Schopenhauer, the will is metaphysical. Barthez could not decide if the life principle was material or not, immanent or transcendent, but he is in agreement with Schopenhauer that it is not conscious. For Nietzsche, the principle of life was what he later called the will to power. Like Schopenhauer’s will and Barthez’s life principle, it is something other than the conscious mind and reasoning intellect. Unlike Schopenhauer’s will, it is entirely immanent in existence.

Nietzsche arguably does leave open the possibility that there is a transcendent element or dimension, insofar as his philosophy, rooted in skepticism and epistemological modesty, does not absolutely deny the transcendent so much as ignore it, since it is not apparent to the senses and is hopelessly mired in abstract concepts and illusions. This insistence on immanence would later be identified as a key characteristic of the school of thought of which Nietzsche would be considered a progenitor, and which would eventually be called “German vitalism”—lebensphilosophie.

Lebensphilosophie

Lebensphilosophie is “life philosophy.” Its translation as “vitalism” has been somewhat unfortunate, since that term already existed in the sciences and denotes a different set of concepts and ideas, although there is sometimes overlap. Frederick Beiser in his recent study of German lebensphilosophie gives the following list of its characteristics:

a completely immanent philosophy, void of all transcendent entities; individualism and relativism in ethics; opposition to pessimism and an affirmative attitude toward life; historicism and hermeneutics in the study of culture and society; and an individualist and relativist conception of philosophy. Lebensphilosophie was the first strictly non-religious philosophy—its first principle was atheist or agnostic—and the first explicitly relativist ethics in the history of Western philosophy.

Although Nietzsche himself did not use the term lebensphilosophie (let alone “vitalism”) to describe his ideas and views, that label came to be applied to him and to other, later thinkers who share some or all of these characteristics. Beiser focuses on Wilhelm Dilthey and Georg Simmel, both contemporaries of Nietzsche. Whereas Nietzsche was a right-wing radical—he endorsed Georges Brandes’ description of his philosophy as “aristocractic radicalism”—Dilthey and Simmel were both political liberals. Thus, from its inception in these three thinkers, lebensphilosophie or German vitalism has been split between its right and left wings.

In his encyclopedic article “Life: Vitalism” for the left-wing Theory, Culture & Society, written in 2006, Scott Lash uses “vitalism” and “lebensphilosophie” interchangeably and gives the following genealogy of vitalist thinkers:

There are three important generations of modern vitalists. There is a generation born about 1840–45 including Nietzsche and the sociologist Gabriel Tarde; the generation born about 1860 including the philosopher Bergson and the sociologist Simmel, and the generation born about 1925–33 including Gilles Deleuze, Foucault and Antonio Negri. Contemporary neo-vitalism can in many respects be understood as Deleuzian. There seem to be two vitalist genealogies. One connects Tarde to Bergson and Deleuze, and the other runs from Nietzsche through Simmel to Foucault. The Bergsonian tradition focuses on perception and sensation while the Nietzschean tradition focuses on power.

What we see here is that, as with Nietzsche himself, lebensphilosophie underwent a kind of rehabilitation and reorganization after the second World War, with its rightist elements being suppressed or misrepresented. This is largely due to the prominence of Gilles Deleuze, who wrote influential books on Nietzsche and Henri Bergson in the 1960s and who considered himself to be a vitalist, famously declaring, “Everything I’ve written is vitalistic, at least I hope it is.”

The genealogy that Lash establishes for contemporary Deleuzian vitalism is not, however, the only branch that grew from the root of Nietzsche’s ideas (or, as followers of Deleuze would prefer to say it, not the only shoot from the Nietzschean rhizome). In his 1932 study The Vitalism of Count de Gobineau, Gerald Spring establishes a quite different genealogy of vitalism-lebensphilosophie. He sees its antecedent in Romanticism, both in Germany and in France, and the development of Romanticism into lebensphilosophie as a result of its fusion with ideas of the active unconscious from the Montpellier vitalists and others.

The romantic theory of the German poets and philosophers amounts practically to a generalization of the vitalism of biological theorists, they were given to extending the vitalistic formulas to all orders of reality. Depreciating mechanism or cold intelligence these German romantics glorified “vital impulse” which they considered to be the underlying principle of all reality. To intellectual analysis which decomposes the whole into its parts and mechanical construction which builds up by means of assembling parts already given, they opposed that obscure power of creation and synthesis working spontaneously from inside outwards which is manifested by what we call life. These romantics recognized this power of life in societies no less than in biological organisms.

Spring’s characterization of vitalism is worthwhile:

Vitalism in this broader sense might be called a philosophy of affirmation since it is anti-ascetic, opposing all asceticism in religion and philosophy and destructive or negative intellectualism. … [Vitalists] are inclined to value intuition more than intellect and to glorify “life” as the ultimate reality. Pragmatism follows from this as a matter of course, for vitalists naturally wish to heighten life and to further it in every way. … [my emphasis]

Much importance is attached by vitalists to instinct or “unconscious spontaneity” which they view as superior to reason or cold intelligence. Instinct, moreover, has its social equivalent in tradition so that vitalists, as a rule, deprecate undue intellectual interference in social evolution, preferring to trust the irrational or non-rational continuity or spontaneity of life itself. Thus eighteenth Century rationalism and the Contrat Social of Jean Jacques Rousseau and their sequel, the French Revolution, are anathema to vitalists. …

Vitalists are advocates of intense living and emphasize the importance of strength of character—one thinks of the cult of energy of Stendhal, Merimée, Gobineau and Nietzsche. Vitalism is anti-intellectual and hostile to rationalism; reason proceeds by means of identity, while life makes for differentiation. Vitalists abhor the abstract notion of man brought into fashion by the “philosophes” of eighteenth Century France and the more logical and consistent among them combat the “égalitaires” and, in particular, the attempt of Rousseau the rationalist to create an artificial equality among men.

Vitalists tend to distrust the dispassionate use of the intellect and to deny the concept of absolute truth, because they favor individual truths. They sympathize with illusion whenever it is seen to favor life.

What Spring describes here is the vitalism of the Right. This line or branch of vitalist thought, from Gobineau, Stendhal and Nietzsche, to Ludwig Klages and Oswald Spengler, has been largely suppressed and ignored since the second World War, only coming to relative prominence once again in the 21st century thanks to the republication of works by Spengler and Klages, and the popularization of Nietzschean vitalism by Bronze Age Pervert.

There are many similarities and overlaps between the vitalist thought of the Right and that of the Left; often the difference is in how certain ideas are applied rather than the ideas themselves. As Jonathan Bowden noted, the Left has always liked the part of Nietzsche’s philosophy which is destructive and critical, particularly towards Christianity. Nietzsche’s rejection of conventional morality informs both the leftist and rightist interpretation of him, though in very different ways. For the Right, Nietzsche’s “immoralism” means that war, slavery, exploitation, and cruelty must be seen anew, not with the condemnatory eye of a moralist but with a biologist’s and anthropologist’s eye, in order to understand their functions in the life process. For the Left, immoralism means something else, perhaps best exemplified by André Gide’s novel The Immoralist, written in 1901 when Nietzsche’s corpse was barely in the grave, in which the main character uses Nietzsche’s ideas as a justification for pederasty and homosexuality. One can see from this example that the split between leftist and rightist interpretations of Nietzsche precedes World War 2.

In my view, the key distinction between rightist and leftist vitalism lies in their different relationship to nature. Rightist vitalism extols and reveres nature, and looks to nature for its understanding of what life is and how it functions. Nature therefore means biology, animal life, and ecology, but with the key understanding that nature is unequal and predatory. This is especially true of Nietzsche and Klages. For leftist vitalism, nature seems to be the enemy, something to be overturned. They seem more interested in the grotesque than in the beautiful. In this way, “leftist vitalism” is something of a misnomer since it is often theory divorced from biological life; the conceptual and logocentric play of the intellect, divorced from the body.

For rightist vitalism, it is not a matter of privileging the body over the mind, but rather, as Jonathan Bowden said, of “bringing the mind and the fist together.” Leo Séra wrote:

I will only say that in some men the strongest thought coincides with the most intense life, and that these men are, or should be, at the top of the tree. … [I]n the highest stages life coincides with thought, and it is only when going down from the two parts of the hierarchical curve that we find either the predominance of life in its lower and more brutal functions, or thought more or less morbid with its abstractions and abstrusenesses. I maintain, however, that for the highest interest of life, its preservation, I incline to the first defect rather than to the second.

Vitalism has some commonality with Buddhism’s critique of the discursive intellect, with its endless verbalizing and fabrications which obscure direct perception and cognition. But whereas Buddhism sees direct perception as a function of the mind (in its original, pure state, which is metaphysical), vitalism, as a secular philosophy rooted in biology, sees direct perception as the instinct of the body. Insofar as Séra inclines towards the body rather than the mind or intellect, he somewhat agrees with Ludwig Klages, for whom the development of the intellect, the conceptual mind, was a kind of cosmic disaster not unlike the way Rust Cohle describes the emergence of human consciousness in True Detective. But vitalism need not be primitivism, an attempt—perhaps futile and impossible—to return to a pre-conscious state of animality and instinct. Rather, it can be the attempt to integrate intellect and instinct, to fuse them into a higher state of mind and being, to make “the strongest thought coincide with the most intense life,” as Séra says. Since man is both body and mind, or soul, regardless of whether one sees them as dualistically separate or as different aspects of the same thing, both should be cultivated to their maximum potential.

In his article, Lash correctly asserts that vitalism is rooted in Heraclitus’ philosophy of flux and becoming, rather than the Parmenidean-Aristotelian tradition of being and stasis. One might say it is Dionysian rather than Apollonian. At the heart of vitalism is the suspicion, and the desire, that life can be something more than it is, something more than “mere life” as Bronze Age Pervert says. The ordinary life which is given is not enough, especially in our day and age. Ludwig Klages wrote of the need for rausch, ecstasy. A half century earlier, Charles Baudelaire described the something more as akin to intoxication:

One should always be drunk. That’s the great thing; the only question. Not to feel the horrible burden of Time weighing on your shoulders and bowing you to the earth, you should be drunk without respite.

Drunk with what? With wine, with poetry, or with virtue, as you please. But get drunk.

At its best, vitalist thought can inspire the quest for this intoxicating something more, in whatever forms it may take.

________________________________

The book which you hold in your hands by Gioacchino Leo Séra is a forgotten classic of Nietzschean vitalist thought. It was published in Italian in 1907 as Sulle Tracce Della Vita (Saggi) and translated into English two years later as On the Tracks of Life: The Immorality of Morality. The English translation was done by J.M. Kennedy, an interesting figure in his own right. He was a British writer and right-wing modernist who wrote for A.R. Orage’s influential periodical The New Age and who translated Nietzsche’s The Dawn for the very first English edition of Nietzsche’s collected works. He also wrote one of the first books in English on Nietzsche’s philosophy, The Quintessence of Nietzsche, and translated Henri Lichtenberger’s The Gospel of Superman: The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche from the French.

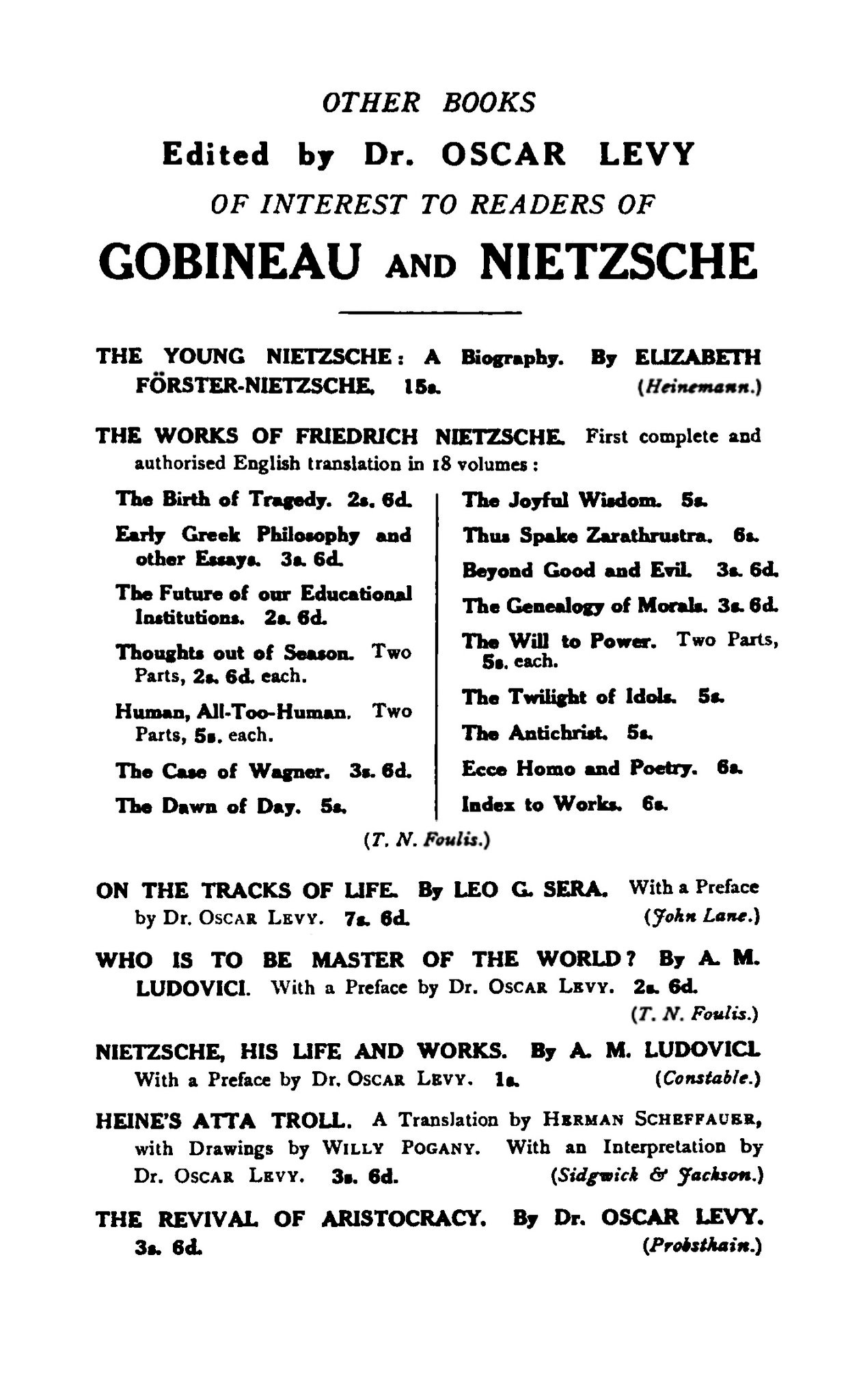

The translation and publication of Séra’s book seems to have happened at the behest of Oscar Levy, the editor of the English translation of Nietzsche’s collected works. Levy wrote a glowing review of the book in the December 7, 1907 issue of The New Age, and also wrote the introduction to the first English edition, which has been omitted here. A contemporary advertisement shows Séra’s book listed alongside volumes by Nietzsche, Anthony Ludovici and Levy’s own The Revival of Aristocracy as “Other Books Edited by Dr. Oscar Levy of Interest to Readers of Gobineau and Nietzsche.”

Before the wars of 1914-18 and 1939-45, Nietzsche was largely seen as a philosopher of “aristocratic radicalism”—that is to say, a proponent of hierarchy, “order of rank,” inequality, selective breeding, and the rejection of all comfortable illusions for the sake of raw, honest truth about life. In this atmosphere it was natural to read him in the same company as Gobineau—fellow theorist of “master races”—and to see both men as representing the same strain of vitalist thought, as Gerald Spring does in his book. It was only after the wars that Nietzsche and lebensphilosophie first fell out of favor and then were rehabilitated in an altered, distorted form.

The work of the early modernist Nietzscheans such as J.M. Kennedy, Thomas Common, Oscar Levy and others represent an initial engagement with Nietzsche’s ideas devoid of political correctness and sheepishness brought about by the trauma of the wars. They were the British Nietzscheans, and they found in the Italian Leo Séra a fellow traveler, but from a different direction. Whereas their thought and writings reflect an essentially Northern worldview, Séra is decidedly Southern and Mediterranean. This is significant not least of all because, as he notes of Nietzsche

His doctrines are the aspiration of the north for the south, of the mind of countries deprived of sun and life for light, for heat, for the blue of the southern sky. … Nietzsche’s work is a southernisation of the northern mind, its refinement, its embellishment.

So who was Leo Séra? Various sources give his birth year as either 1870 or 1878 in Florence. He studied medicine and surgery in Rome, graduating in 1903. Most of his biographies online are brief and jump immediately to his career as a professor of Anthropology from the 1920s onward. He taught at Pavia, Milan, and then at the University of Naples beginning in 1926. Before this he was in Rome, Florence, and Bologna, conducting anthropological research in various museums. While at Pavia he founded the Giornale per la Morfologia dell’ Uomo e dei Primati (Journal of Human and Primate Morphology) which was the first journal of its kind, and which ran from 1917 to 1923. Many of the articles published in the Journal were by Séra himself. The Giornale ceased publication because Séra was rendered blind by an illness, a condition which would continue for the rest of his life. He is remembered today mostly for his work in primatology, craniometry and human origins. He was one of the last proponents of the theory of polyphyletism, the idea that human beings have more than one evolutionary ancestor. He was also the first to propose what is now called the Aquatic Ape Hypothesis, that there was an aquatic phase of human evolution, a theory which continues to be investigated and debated today. (The theory is summarized in the first chapter of Desmond Morris’ The Naked Ape.)

Séra’s academic work belongs to the later part of his life. His early years, during which he wrote On The Tracks of Life, are not discussed. In the memoirs of Eva Kühn Amendola, a Lithuanian woman associated with the Futurist movement, she mentions that Séra was part of the Florentine cultural circle centered around the Theosophical Society, though it is unknown whether he was a member. If so, the Theosophical doctrine of “root races” may have provided inspiration for his later polyphyletist ideas. That Séra the Nietzschean was part of the milieu from which Futurism emerged makes perfect sense, since Futurism was more influenced by Nietzsche than was Dada, Surrealism or any of the other avant garde art movements of the early 20th century.

Séra unquestionably knew Eva Kuhn’s husband, Giovanni Amendola. The appendix to this book is largely concerned with responding to a review by Amendola, whom he calls his “good friend.” Amendola is remembered today for being an opponent of Fascism who was attacked by Blackshirts in 1925 and later died from his injuries. Séra, despite holding Nietzschean views that would undoubtedly be considered far-right today, never joined the Fascists, perhaps because of what happened to his friend.

In 1935 Séra wrote the entry on “Race” for the Encyclopedia Italiana, which explicitly rejects the National Socialist doctrine of race and the existence of Jewish, Italian and Aryan races. This was Mussolini’s stated position at the time, and so it is unclear whether Séra himself believed this or whether he was pressured to conform to Mussolini’s views.

His views in 1907 were certainly not such. In On The Tracks of Life he wrote:

So we may see that, prepared by their vigorous social structure, and having arrived at the period of military civilisation, the late descendants of the former emigrants marched back again to the south, this time as invaders and conquerors. Athirst for heat, love, and power, they descended into the countries of brightness, the land of dark-eyed and dark-haired women, and by sheer strength and war founded their kingdom. Thus did the Goths and the Vandals in Spain, thus the Franks in France, thus the Goths, the Lombards, and the Huns in Italy. Similarly, it should seem that the Greeks were invaders who had come from the north, and imposed themselves as aristocratic and governing classes upon the native element, and that, having in time forgotten their own origin, they regarded as barbarians those who were not native Hellenics.

But the finest and greatest example of this process is shown us by the Aryan race, which, having sprung up in the Pamir plateau, descended into India and founded the greatest and most superb of military aristocracies.

On the Tracks of Life is a remarkable exposition of vitalist thought which was in many ways a century ahead of its time. It is firmly rooted in biology because of Séra’s medical and anthropological training. Like Nietzsche, he is more on the side of scientific skepticism than of speculative and unfounded theories. He praises Hermann von Helmholtz, who was an opponent of vitalist theories of biology in favor of a more strict materialism. Considering that hormones were only discovered a few years before the book was written, it is remarkable that he was already speculating on their importance for individual character and development, as he does in chapter 4. Likewise his observations (echoing Nietzsche again) on the importance of nutrition and diet:

A poor and deficient allowance of food, that is to say a dynamogenic supply, while it makes people all the more willing to submit to the yoke of servile labour and organic impoverishment, is likewise an instrument of political oppression, for weak and badly fed individuals are far from desiring liberty and independence, or, if they do sometimes feel such a desire, they do not possess the intellectual power of discovering what means they should employ to attain their object.

Séra also shows a keen grasp of human psychology. Indeed, two of his primary influences are Nietzsche and Stendhal, two of the greatest psychologists of the 19th century, each of whom has a chapter dedicated to his work here. The book opens with a chapter originally titled simply “Love,” which we have changed here to “Love and Lust” since its true subject is sexuality and breeding as they relate to society. He is fully in accord with Nietzsche’s statement that “The degree and kind of a man’s sexuality reach up into the ultimate pinnacle of his spirit.” Sexuality is at the core of Sera’s conception of vitalism; for him, vitality is virtually synonymous with virility. He develops the idea that “sexuality and sociality are connected by the closest ties; but this relationship is antagonistic: in complete opposition. Sociality is in function the reverse of sexuality …”

Sexual, aristocratic, beautiful, are conceptions which are closely related to one another, if not, indeed, the same thing seen from different aspects. Thus I have already said that love, dominion, and genial creation have a common root and a common soul.

It is for this reason that the aristocratic individual is shown to be almost an enemy of sociality and of morality, because he is the representative, against these, of rights of race, strength, and virtue which tend, in their greatest and most glorious manifestations, to increase and perpetuate.

He also anticipates some of the insights of Rollo Tommassi, Heartiste and others, a hundred years earlier, as for example when he formulates the principle which Rollo would later call “Alpha Fucks, Beta Bucks”:

From this point of view woman has the sharpest insight! With a single penetrating look and synthetic discernment she values and adjudges a man, weighs up in an instant all that she can draw from him and which she thinks may be useful to her; so that while she will submit her entire self with all the humiliation of a slave to one man in order to obtain even a kiss from him, she will make another pay a high price for her body, the price, that is, of . . . matrimony.

Séra’s psychological insight is also on display in the chapter on “Modesty and Shyness” which prefigures Jung’s later concepts of introversion and extroversion.

Chapters 2-4 concern the origin of society in the different castes of men. He defines what he calls the aristocratic spirit as:

A detached individualism, courage in every form, the spirit of initiative and enterprise, the love of adventure, of war, and of the chase, of the unknown and of the unexpected, are the distinguishing traits of those individuals who belong to the first type, traits which denote a healthy and vigorous nature. Leisure is their natural state, as it was also the state of primitive humanity, of which, indeed, they possess many of the characteristics. These are the men who are called “rulers,” “masters,” “governors.”

The theme of leisure, which Séra treats and defends considerably, would later be developed by the Catholic philosopher Josef Pieper in his 1947 book Leisure: The Basis of Culture. In contrast to the prevailing and various worker ideologies of the time, Séra views work as such the same way that the Greeks did: as drudgery that drains the spirit of life. “[My] principal thesis—the identification of aristocracy, physical superiority, and repugnance to work.”

The key question for Séra is this:

Does the most desirable and highest advantage of society consist of well-being assured to all—the greatest happiness of the greatest number—in the tendency to mediocritise all abilities; or in opposing and confirming the differences, in widening the gap between rich and poor, between exploiters and exploited?

Those who accept the first solution are democrats in all the different senses of the word; those who accept the second are aristocrats: and those who accept the first agree to accept for humanity a future resembling a deep, low-lying bog.

Like Nietzsche, he sees the Greeks as the high point of human achievement.

Hellenic civilisation signified perhaps the culminating point of the history of civilisation on earth, as it showed a perfect balance between interiority and exteriority, between form and substance. This correspondence and harmony between real and ideal, between thought and execution, between the beautiful and the true, glittered perhaps like a transient meteor in the Greek sky. We at least with our Renaissance saw only a very much diminished light derived from it.

Central to Séra’s worldview is “the psychological contrast between North and South” and their interplay in the development of civilizational and historical trends. He develops this idea throughout the book, especially in chapters 3 and 8. While his perspective is certainly centered in his Southern place of origin, and is perhaps somewhat influenced by the Mediterraneanist ideas of Giuseppe Sergi which were prevalent at the time, he is not at all chauvinistic or bigoted, and takes Nietzsche’s ideal of the “Good European” as his own. In chapter 9, “Social Rhythms,” he anticipates some of Spengler’s ideas about culture and history, and makes some remarkable predictions about the rise of Germany in the 20th century. In the following chapter on the nature and creation of genius, he writes that “genius is liberation, an aristocratic mind’s finding itself after having been held prisoner by inferior conditions.”

_________________________________

As for the change in the book’s title, and relegating its initial title to subtitle, there are two main reasons. First, “The Immorality of Morality” seems to have been chosen for its shock value for a 1909 audience rather than for how aptly it describes the subject and contents of the book, which is not primarily or even secondarily a critique of morality. (Likewise, Séra’s subtitle in Italian was simply “Essays,” implying that the chapters are individual and standalone, but they are not—the book is a coherent whole and should be read as such.) The real subject of the book, as with any good book of lebensphilosophie, is Life. Although Séra does not use the term “vitalism,” the word vitality shows up repeatedly in his evaluations as a principle criterion, as when he says that “the ideal of the higher man has its origin in the expansive instinct of a growing vitality, of a vitality which, having been compressed and diminished, returns to primitive grandeur and strength.”

Of his philosophical position, Séra writes that: “I am certainly neither a materialist nor a positivist in the customary sense of the words, perhaps not even a realist; but neither do I feel myself to be an idealist.” What he is, as I hope I have established here, is a vitalist, and that is the philosophy which his book expounds.

As for the original title, it has been retained as subtitle both because it was the author’s choice and because it evokes the search and the quest that any good vitalist philosophy ought to inspire and guide: for more truth, more power, more life.

This book, then, is for “the higher man, the man who examines himself and finds in his own being the traces of a free and healthy life, of a profound force long handed down from generation to generation, who becomes aware of his own nobleness …”